Research

Overview

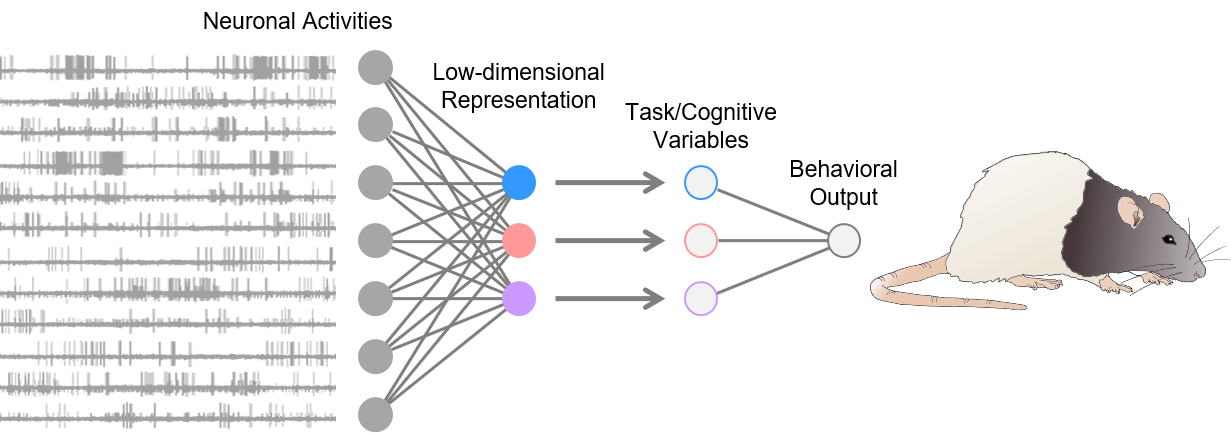

The lab’s research interest has coalesced around a desire to understand the neural circuit mechanisms of animal behavior and cognition. We use in vivo electrophysiology as a primary tool, combined with complex behavioral tasks, optogenetics, and computational tools, to map neural dynamics embedded in the neural population activities—primarily in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus—to the task or cognitive variables that underlie associative learning, memory, and decision-making. We are also interested in how these neural representations and their behavioral functions would change in neuropsychiatric disease conditions such as addiction, depression, and schizophrenia.

How do we understand the world around us?

Plenty of evidence has shown that our brain likely constructs a mental model of the surrounding environment. Such a model, or cognitive map coined by Edward Tolman in the 1940s, accounts for complex relationships between various parts of the environment, including sensory stimuli, events, and consequences caused by actions. It is believed that we use these models to attend, perceive, predict, learn, remember, decide, and generate actions—spanning the triad of perception, action, and cognition. Thus, to interrogate how we understand the world, it is necessary to figure out how such a model is instantiated through the firing activities of many single neurons, the building blocks of our brain.

A famous quote often attributed to the British statistician George Box: “all models are wrong, but some are useful.” Although it was originally a comment on statistical models, it might also be valid for cognitive maps—we do not build a mental model that captures every detail of the environment like a camera. But instead, we build one most useful in maximizing utility in a complex world. That said, our cognitive maps won’t be necessarily a true reflection of reality but are tailored to meet the task demand at hand (i.e., a “bespoke” cognitive map), which is supported by our recent work in the orbitofrontal cortex (Zhou et al., Curr Biol, 2019a) and hippocampus (Zhou et al., Curr Biol, 2019b) .

Another vital feature of the cognitive map is that it should be dynamic or evolving in time. For example, right after a life experience, such as doing a unit-recording experiment in the lab, we would hold a vivid memory of the episode for a while, including when and where the event has happened. Over time, these details fade away, but more abstract and generalizable knowledge—how to record single-unit activities in behaving animals—is formed and maintained. Consistent with this idea, we have seen neural ensemble activities in the orbitofrontal cortex that convert from detailed to more schematic task representations (Zhou et al., Nature, 2020).

The neural mechanisms of cognitive maps and schemas (i.e., generalized cognitive maps) are still largely unknown. However, many exciting hypotheses have been proposed, such as that the mental models in the hippocampus are more episodic while those in the prefrontal cortex are more schematic. A lot of exciting and essential work needs to be done in testing these and other fascinating ideas. Moving forward, the lab will focus on the following questions.

- How are different mental models—from episodic to schematic—learned and organized in the brain?

- How do prior experience and knowledge guide new learning and behavior through neural representations of these models?

- How are these neural representations and their behavioral functions altered in neuropsychiatric conditions such as addiction, depression, and schizophrenia?

Methodology

To answer these questions, we use an integrative approach derived from behavioral, cognitive, systems and computational neurosciences.

- Carefully-designed complex behavioral tasks to isolate the task or cognitive variables of interest, independent of sensory and motor confounds.

- Large-scale in vivo electrophysiological recording and calcium imaging.

- State-of-the-art multivariate analyses including machine learning to read specific information from both single-unit and neural-ensemble activities.

- Neural perturbation methods such as optogenetics and chemogenetics for causal inference.

- Computational modeling.

Single units on the oscilloscope

Calcium imaging with GRIN Lenses

Hippocampus CA1, 30 frames/sec, 3x speed; Credit: Huixin Lin